Table Of Content

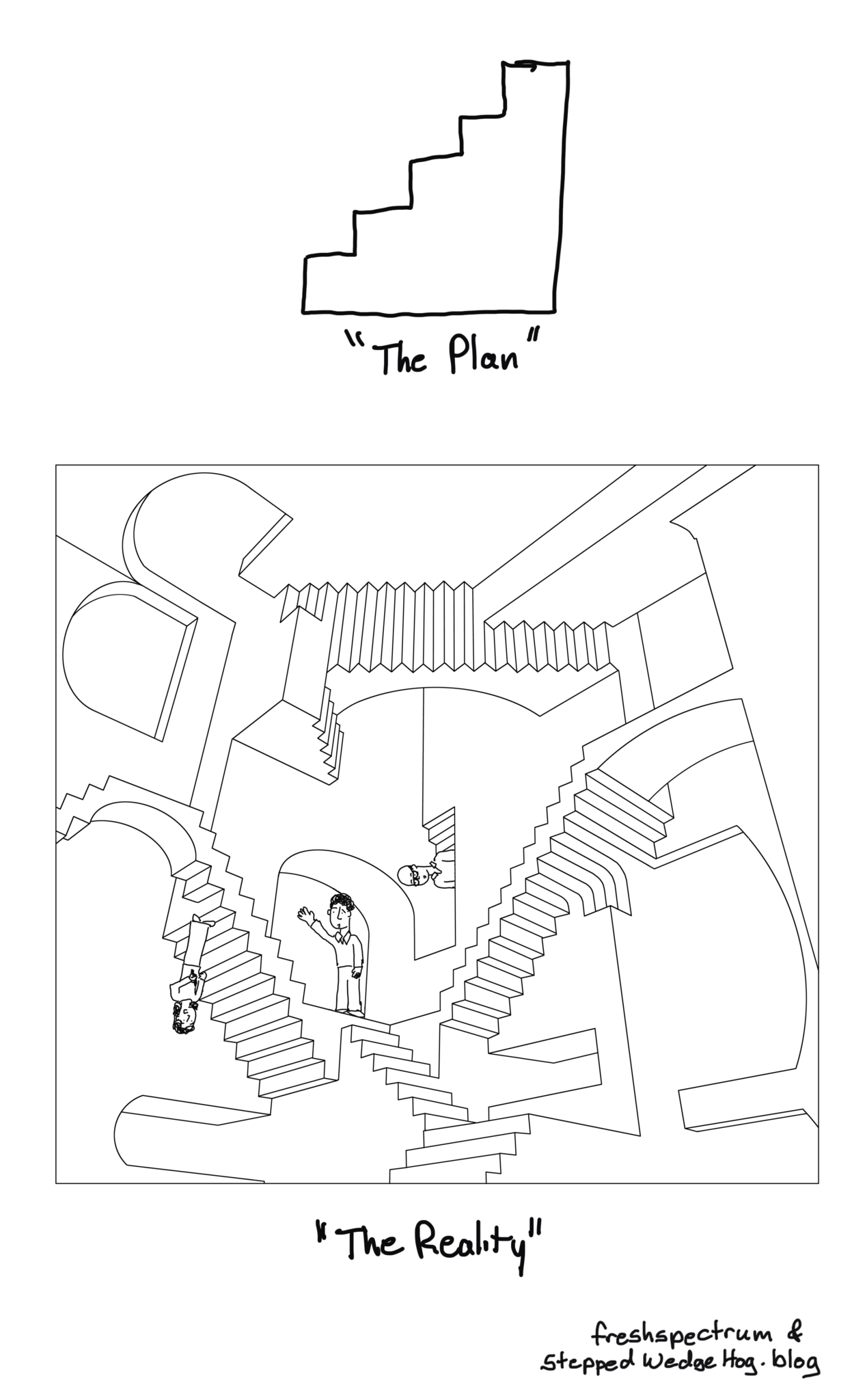

Determining the order in which communities received the intervention at random would have been demonstrably impartial and hence a fair way to allocate resources. From the scientific point of view, randomisation would eliminate allocation bias and the stepped wedge deign would have offered a further opportunity to measure possible effects of time of intervention on the effectiveness of the intervention. Since no pre-intervention measurements were undertaken, it was also impossible to separate the effects of the Sure Start programmes from any underlying temporal changes within each community and these effects could also have been investigated through the use of a stepped wedge design. Stepped wedge designs are relatively uncommon in existing neurosurgical trials, but they can provide a robust design option for future studies. Besides the Early 2RIS trial (Figure 1), we identified four additional SW-CRT examples related to neurosurgery66–69 and summarized them in Table 3.

December 7, 2022: Ethics and Regulatory Grand Rounds Series Explores Stepped-Wedge Designs This Friday - Rethinking Clinical Trials

December 7, 2022: Ethics and Regulatory Grand Rounds Series Explores Stepped-Wedge Designs This Friday.

Posted: Wed, 07 Dec 2022 08:00:00 GMT [source]

Reporting of stepped wedge cluster randomised trials

The current study aims to update neurosurgeon scientists on the design of stepped wedge randomized trials. We can only make conclusions for studies that enroll primary care practices as the unit of enrollment and randomization. However, we believe the identified themes are high level and might apply broadly to health services and organizational research. We took steps to minimize bias and confirm accuracy by checking interpretation of findings across all grantees. Alternative approaches that ensure confidential 1-on-1 interviews might have resulted in different or additional insights.

Challenges

The first is to estimate the average intervention effect across all exposure periods, or time average treatment effect (TATE). The second option is to estimate the intervention effect at a specific time period, or point treatment effect (PTE). Finally, the third option is to estimate the long-term treatment effect (LTE), or the intervention effect at a later time point when the intervention effect is thought to have stabilized. If this later time point corresponds to the final time period in the trial, then the LTE can be estimated with the PTE for the final time period. The choice of estimand depends largely on scientific relevance and investigator interest, but in general tests for the TATE will be more powerful than those for the PTE or LTE.

Associated Data

The key feature of the design is the unidirectional crossover of clusters from the control to intervention conditions on a staggered schedule, which induces confounding of the intervention effect by time. The stepped wedge design first appeared in the Gambia Hepatitis Intervention Study in the 1980s. However, the statistical model used for the design and analysis was not formally introduced until 2007 in an article by Michael A. Hussey and James P. Hughes. Since then, a variety of mixed-effects model extensions have been proposed for the design and analysis of these trials.

The depression management trial (example 3) is an example of an open cohort study design, with some patients remaining in the study for the duration, and others joining the study when they become a resident of a care home. The EPOCH trial (example 4), based on hospital emergencies, is a good example of a cross-sectional study. In the evaluation of interventions delivered at the level of a general practice, hospital ward, or hospital where it is not possible to randomise individuals, randomisation may be carried out at the level of the cluster.10 There are broadly three types of cluster trials to choose from (illustrated in fig 1⇓). In the conventional (parallel) cluster randomised trial, clusters are randomised to either the intervention or control arm at the start of the trial and remain in that arm for the duration of the study (fig 1a).

Just as simple as calculating the limits of confidence intervals is statistical testing of the null hypothesis that the “true” treatment effect ? Both authors contributed to the conceptualization of, drafting, reviewing and editing the manuscript. SWGRTs should only be used when all efforts to implement a more conventional parallel GRT have been exhausted.

The first empirical example of this design being employed is in the Gambia Hepatitis Study, which was a long-term effectiveness study of Hepatitis B vaccination in the prevention of liver cancer and chronic liver disease [4]. In the situation of an underlying temporal trend, an intervention that at first seems to be effective might no longer be when adjustment for calendar time has been made. It might be that, external to the study, there was a general move towards improving patient outcomes, perhaps the very initiative which prompted study investigators to instigate the intervention in question. This phenomenon has been described as “a rising tide.”25 On the other hand, an intervention may be effective, yet there still may be a real underlying temporal trend, although this may be attributable to contamination. In the Matching Michigan study (example 5) these explanations were explored as possible reasons for the finding of no effect of an intervention that in other settings had been very positive. While researching the most comfortable wedges, we focused on picks from well-known brands and those that specialize in stylish and supportive footwear.

This makes blinding of those assessing outcomes particularly important in protecting against information biases, particularly where outcomes are subjective. None of the studies in the sample provided enough detail to determine whether outcome assessments were blinded, with one study [14] deciding not to blind assessors to help maintain response rates. The intervention in this study involved improvements to housing, with health and environmental assessments undertaken in participants' homes so that participants would not have to travel to a 'neutral' location. While the stepped wedge design offers a number of opportunities for use in future evaluations, a more consistent approach to reporting and data analysis is required. The stepped wedge is a pragmatic study design that reconciles the constraints under which policy makers and service managers operate with the need for rigorous scientific evaluations. While researchers may believe an evaluation of an intervention is required, it is decision makers (that is, politicians and managers) who control resources for system change.

Authors

The heterogeneity of analytical methods applied in the studies suggests that a formal model considering the effects of time would help others planning a stepped wedge trial and we will present our exposition of such a model in a subsequent paper. A recent paper by Hussey and Hughes [25] also provides detail regarding the analysis of stepped wedge designs. Two particular statistical challenges are controlling for inter-temporal changes in outcome variables and accounting for repeated measures on the same individuals over the duration of the trial. The stepped wedge is a novel cluster randomised controlled trial design, emerging in the field of service delivery as well as policy evaluations. Finally, statistical analysis of data generated by SW-CRT design is complicated by the partial confounding of intervention effects with time as well as clustering of observations (eg, repeated measures on individual patients within primary care practices). Challenges such as changes in intervention effects over time might be more likely in SW-CRTs because they generally take longer than alternatives.

The SW-CRT design can have a power advantage over alternative designs, such as the parallel CRT design, when the intracluster correlation is larger. Intracluster correlation is larger when outcomes for a practice are more similar than those across practices. Grantees acknowledged that this might be difficult to determine beforehand, especially owing to recruitment challenges (described below) and if there are electronic health record (EHR) inconsistencies across practices. Dr. Li is an Assistant Professor of Biostatistics at the Department of Biostatistics, Yale University School of Public Health.

Currently, simple randomisation is predominantly used, but researchers should consider the use of stratified and/or restricted randomisation. Trials should generally not commit resources to collect outcome data from individuals exposed a long time before or after the rollout period because these data contribute little to the primary analysis unless strong assumptions are made. Incomplete designs have been proposed and can allow a more flexible choice of the number of steps and step length.